In Matthew’s account of Jesus’ polemic against the Pharisees (my Bible titles the 23rd chapter of Matthew “The Seven Woes”), Jesus says to the crowd and his disciples:

“The teachers of the law and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat. So you must be careful to do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach. They tie up heavy, cumbersome burdens and put them on other people’s shoulders, but they themselves are not willing to lift a finger to move them.”

As I imagine most of us (certainly myself) were sitting comfortably in our seats at church this morning, considering just how terrible the Pharisees were, our pastor followed this passage with the question, “Lest we become prideful, we must ask ourselves, ‘On whom am I placing heavy, cumbersome burdens without being a part of the work?'” Said another way, I am speaking the truth but withholding active love and grace?

Immediately a few of my math students came to mind. For various reasons each of them is struggling to survive in my class, reasons which can basically be summarized as a lack of willingness to do the hard work that is required to be successful in this class. After a rough test last week, my plan was to pull each of them aside tomorrow and have “the talk,” which would go something like this: “Suzy, I’m going to be honest with you, this class is only going to get more challenging as the year goes on. It’s time to buckle up and resolve to do the hard work so that you don’t find yourself drowning a month from now.”

Okay, so I would probably be more gentle with them than that, but regardless of my tone, this is the message they would hear: it’s hard now, soon it will be impossible, and it’s up to you to dig yourself out of this hole.

How Pharisaical of me. Why do I do this? Because I get tired. Because I don’t have time. Because I have to keep moving and finish the curriculum. Because I have to prepare these kids for what it’s going to be like in high school.

All of these excuses are at once true as well as invalid. The real reason I tend to stack burdens on these kids’ shoulders without going the extra mile to help them is because I’ve forgotten about all the people in my life who have not only carried my burdens but have carried me as well. I have forgotten about all the times Jesus has walked with me where either I didn’t want to or didn’t think I could go.

Lord forgive me.

Lest we become like those Pharisees, our instinctive posture toward our students must be one of love and grace. But this need not be a “cheap grace” of which Bonhoeffer speaks. On the contrary, I think it is a good and right thing to invite our students to be a part of their own redemption process. In his book The Great Omission: Reclaiming Jesus’s Essential Teachings on Discipleship, Dallas Willard says, “Grace is not opposed to effort, it is opposed to earning. Earning is an attitude. Effort is an action. Grace, you know, does not just have to do with forgiveness of sins alone.” The “acted faith” is what I believe Jesus calls us to when he says, “Follow me.” This is discipleship. It is by God’s grace that we are invited into a life of transformation into his likeness.

God’s grace in my life has looked just like this–it has been an active, transforming grace that is rewriting my story, a revision with which I have been invited to take part. This journey has led me through some seemingly impossible circumstances, but God’s presence has been steadfast, just as it was with Moses, Abraham, Joshua, Gideon, and many others who took an active role in God’s redemption plan.

I am reminded of the moment in The Magician’s Nephew, when Aslan turns to Digory, who by now realizes that it is because of his own actions that evil (in the form of Jadis) has been unleashed in the newly-created Narnia. Aslan asks Digory if he’s ready to undo the wrong he has done to Narnia, and Digory hems and haws about not knowing what he can do, what with Jadis disappearing and all, to which Aslan simply restates his original question: Are you ready? Digory answers in the affirmative, but cannot help–despite knowing that the Lion is not someone to be bargained with–but throw in a plea for Aslan’s help in curing his ill mother back home. The next passage is worth quoting in full:

“Up till then he had been looking at the Lion’s great feet and the huge claws on them; now, in his despair, he looked up at its face. What he saw surprised him as much as anything in his whole life. For the tawny face was bent down near his own and (wonder of wonders) great shining tears stood in the Lion’s eyes. They were such big, bright tears compared with Digory’s own that for a moment he felt as if the Lion must really be sorrier about his Mother than he was himself.”

Do I pause to consider that something else besides my math class might be going on in my students’ lives? Do I seek to know them, to empathize with them, to grieve with them?

After this moment of real human connection, Digory finds new resolve to take on the mission Aslan has set before him. Even though “he didn’t know how it was to be done . . . he felt quite sure now that he would be able to do it.”

Do I give my students a reason to believe that they can do what they don’t quite know how to do?

Next Aslan asks Digory to describe what he sees to the West. “I see terribly big mountains, Aslan,” Digory replies. And this is only the first of three imposing mountain ranges that Digory describes. Quite plainly, Aslan tells Digory’s that his journey will take him straight through those mountains.

Am I honest with my students about the challenges that lie ahead? Do I invite them to assess the journey, or do I simply describe it for them?

Once Digory is informed of just what was going to be required of him on this journey, he says quite honestly to Aslan, “I hope, Aslan, you’re not in a hurry. I shan’t be able to get there and back very quickly.”

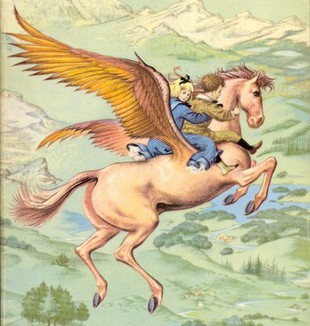

And Aslan replies, “Little son of Adam, you shall have help.” Turning to the cabby’s horse, Strawberry, Aslan transforms him into the winged Fledge.

Do I offer help to my students on what might seem an impossible journey? To what lengths am I willing to go? Sometimes it takes some out-of-the-box thinking, like putting wings on a horse. In addition to inviting my students on an arduous journey, am I simultaneously embodying Christ’s active love toward them? Am I walking alongside them?

Am I working as hard for them as I want them to work for my class? Or, am I stacking heavy burdens on their shoulders and wishing them the best on their journey?

“But I’m not a miracle worker,” I have found myself saying. I can’t make a horse fly. What do I do when I feel like I have done everything?

Our pastor ended this morning by asking the question, “Do we petition the Holy Spirit as fervently as we petition those who we want to see change?”

Do I forget that ultimately it’s not up to me? How often do I pray for my students by name? How often do I invite the Holy Spirit into my classroom?

After all, there is a lot more at stake here than my students learning math. Their time in my classroom is but a very short chapter in a very long book. Nevertheless, their journey at this moment includes my math class and, therefore, it includes me. How will I make the coincidence of our paths count?

Somehow Christ is able to say, “Take up your cross and follow me,” but also say, “My yoke is easy and my burden is light.” This is the scandalous love of the gospel. I still don’t really get it. But I know it. And I want my students to know it. And I do not want to miss the opportunity to embody this kind of love for them. I may not be able to make a winged horse, but–like Polly, who sits right behind Digory on Fledge’s back–I can certainly go with them on this leg of their journey.